Check out this short piece "attempting" to condense the recent story on potentially venomous sinornithosaurs. The piece was written by New York Daily News staff writer Ethan Sacks, who does not understand one word of the subject he's covering.

The headline:

"Venomous velociraptor: Scientists discover sinornithosaurus dinosaur spit poison at prey"

*HEADDESK*

I can guarantee you with 100% certainty no scientist or press release even remotely said anything like this.

What they probably told him/what he probably read on other news sites: "The dinosaur Sinornithosaurus, a relative of Velociraptor, was venomous, like the spitting dinosaurs in Jurassic Park."

What Sacks heard: "Velociraptor's relatives were venom-spitting dinosaurs, like in Jurassic Park!"

Way to make the world a dumber place, Ethan Sacks.

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

Monday, December 21, 2009

Venomous Dinosaurs

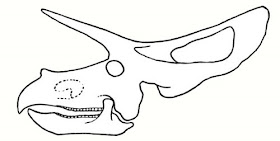

Above: Illustration of a Sinornithosaurus skull.

A few of you may remember a little 1993 picture called Jurassic Park. In the film as in the novel it was based on, a point was made of showing how unpredictable cloning extinct organisms could be, and that we would not be able to anticipate all the dangers dinosaurs posed just from their fossil remains. To illustrate this, author Michael Crichton invented the idea that the basal theropod Dilophosaurus was venomous. This was, of course, completely fictional and only present to make a philosophical point. There is no evidence whatsoever that this dino had venom, let alone could spit it like a cobra, let alone had a ridiculous display like a rattling frill-neck lizard (added only for the movie).However, while Dilophosaurus in particular was probably not venomous (and if it was, the late Crichton should be hailed as a prophet for picking that specific dino out of his... orifice), this doesn't rule out the possibility that some dinosaurs were. Poison or venom of come kind exists in a wide selection of modern vertebrates, from amphibians, to lizards (like the gila monster and Komodo dragon) and even birds such as the Hooded Pitohui, which is very aptly named, as the neurotoxins in its feathers cause predators to promptly spit it out.

There has in the past been some goss to the effect that we have evidence for venomous dinosaurs (the difference between venom and poison: poison is ingested or absorbed from prey to predator, venom is injected from predator into prey). A 2 cm long tooth with a longitudinal groove, reported from Mexico in 2001, was suggested to come from a venomous theropod.

Those grooves, which are actually present in most theropod teeth to some extent, are the issue of a new controversy over a paper on the Chinese dromaeosaurid Sinornithosaurus, which we've covered before regarding it's hind wings, or lack therof. A new study looks at the unusually positioned gooves on sinornithosaur teeth, and speculates that these could have delivered venom. The researchers even identify an opening in the upper jaw bone where the venom gland may have been. (left: Sinornithosaurus by FunkMonk. Licensed.)

Those grooves, which are actually present in most theropod teeth to some extent, are the issue of a new controversy over a paper on the Chinese dromaeosaurid Sinornithosaurus, which we've covered before regarding it's hind wings, or lack therof. A new study looks at the unusually positioned gooves on sinornithosaur teeth, and speculates that these could have delivered venom. The researchers even identify an opening in the upper jaw bone where the venom gland may have been. (left: Sinornithosaurus by FunkMonk. Licensed.)This is exciting stuff, but take it with a grain of salt. Ed Young does a good job covering the situation at his blog. Basically, it's entirely possible that the grooves are simply features typical of other theropods. Many animals have grooves on their teeth to negate any suction that would occur when pulling the tooth out of flesh. However, Young also reports that Bryan Fry, who discovered the venom of Komodo dragons, has stated that grooved never occur on the posterior side of the tooth surface except in venomous animals, which sounds pretty convincing.

The authors of the new paper cite the length of the grooved teeth as evidence that they were "fangs", but it really just looks like they're out of socket, the way many theropod skulls are mounted in museums. T. rex famously have 6-inch teeth, but that includes the roots. Really, only 2 or three of those inches would protrude from the jaw. Fossils that have been crushed and distorted are also susceptible to out of socket teeth making the dentition look more formidable (and more fang-like) than it really was.

Above: T. rex mount with teeth dangling out of the mouth like it just finished a brutal hockey game. Photo by Quadell from Wikipedia. Licensed.

Above: T. rex mount with teeth dangling out of the mouth like it just finished a brutal hockey game. Photo by Quadell from Wikipedia. Licensed.Obviously more investigation needs to be done, but famous TV personality Dr Tom Holtz is on record saying he evidence is weak, so let's not be too hasty with conclusions here.

Thursday, December 17, 2009

V-D Day for Matt Wedel

Quick epilogue to the Clash of the Dinosaurs quote-mining incident, Matt was able to talk to someone at the Discovery Channel (which aired and distributes but did not directly produce the special). Discovery promised not to re-run the show until the offending segment was removed, and it will be fixed on the DVD and Blu-ray release as well. Congrats Matt, and way to go Discovery Channel! It is definitely the network's responsibility to ensure the integrity of the shows they air, and Discovery is certainly living by its policy here.

You can read Matt's latest post at SV-POW.

You can read Matt's latest post at SV-POW.

CotD: The Saga Continues

Above: If Wedel had used the words "laser" and "armor" at any time during his interview, CotD would have looked like this. Not that I'd complain.

Above: If Wedel had used the words "laser" and "armor" at any time during his interview, CotD would have looked like this. Not that I'd complain.Matt Wedel has posted his experiences trying to chase down what exactly went wrong with his infamous interview segment in the Discovery Channel and Dangerous, Ltd.'s special Clash of the Dinosaurs. You can read the letter where Dangerous, Ltd. admits that they quote-mined him like creationists and had him spouting nonsense discredited before he was born as if it were fact, here.

An excerpt of the good part:

"In your email, you said: ‘Someone in the editing room cut away the framing explanation and left me presenting a thoroughly discredited idea as if it was current science.’ In your interview you carefully set out a context in which you made your argument, a context that was perhaps not included in the show as carefully as it could have been. Whether this was in the interests of brevity or not, I entirely appreciate your position. We had no wish to suggest you were presenting an old, discredited argument, we were simply working on the show ever aware of the demands of our audience. This does not excuse a part of the program which was perhaps not edited with as much finesse as it could have been and consequently I will make your concerns clear to the production team in the hope that we may avoid such situations again."

Note that they don't apologize or say they'll fix this in future broadcasts of the show (and if it's like other Discovery shows, it will be running on a loop for months). The best part is that the lame excuse email makes clear Dangerous' motivations: They only wanted to accomodate the needs of their audience and hold everyone's attention. That means this was done ON PURPOSE, because the truth was TOO BORING.

Discovery Communications and their affiliate production companies don't care about science. Sorry if I sound like Kanye, but this is true and everybody needs to learn this fact. The only goal here is to keep eyeballs glued to the TV with whatever fake nonsense they can piece together from edited sound bites given by experts hired only to bring a veneer of credibility. They decide what they want to say and show, then hire experts and interview them until they've said enough vowels and consonants to piece together a convincing ransom-note narration.

Not that this wasn't already obvious, but there it is in print.

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

CotD: More Ugly

In last week's post on Clash of the Dinosaurs, I discussed the pros and cons from a viewers perspective. To sum up, I thought it was decent but flawed, with too much repetitive CGI and science made palatable by the presence of real experts like Matt Wedel.

Matt has chimed in with his own post about the special, which points out some really, really troubling behind-the-scenes behavior on the part of the producers, and proves once and for all that Dangerous Ltd., a production company for venues like the Discovery Channel, are not interested in science. Well maybe initially, but when it comes time to air, snazzy gee-whiz-wow anti-facts are all that matters to them. From Matt's blog post:

"I said something like, 'There was this old idea that the sacral expansion functioned as a second brain to control the hindlimbs and tail. But in fact, it almost certainly contained a glycogen body, like the sacral expansions of birds. Trouble is, nobody knows exactly what the glycogen bodies of birds do.'"

...

"Somebody in the editing room neatly sidestepped the mystery of the glycogen body by cutting that bit down, so what I am shown saying in the program is this, 'The sacral expansion functioned as a second brain to control the hindlimbs and tail.'"

Matt is rightly extremely pissed about this and I'm right there with him. A show supposedly about science edited the words of a sauropod expert to espouse the idea, in a national TV program airing in the year 2009 (note: not year 1939!) that sauropods had a second brain in the tail.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Ok? Good. This is like the paleo equivalent of a documentary about Darwin, featuring Darwin on film, then editing Darwin's words to make it sound like he was a creationist. Did I just call Matt Wedel the Darwin of sauropodology? You decide.

To sum up, the only thing worse than science reporting in the news, are science "documentaries" on TV. I'd have no problem if Discovery Channel had called this a science fiction special, but they did not, and that's flat-out lying.

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

The Baddest Dino You've Probably Heard Of

Yesterday, I covered the first part of the Discovery Channel's night of dinos on December 6th. After Clash of the Dinosaurs, Discovery aired a less-promoted special on Spinosaurus (apparently the first in a series) called Monsters Resurrected: Biggest Dino Killer. According to Tom Holtz, who was interviewed for the show, a second (apparently better, from his POV) special focusing on Acrocanthosaurus will air in the coming weeks or months. The point of this series seems to bring focus to lesser known giant carnivorous theropods.

The "lesser known" conceit was the first in some bizarre choices, pseudo-errors, and misleading narration/imagery to come from this special. Altogether, I can't say it was "better" than CotD, but to me it was heaps more interesting because of all these little quirks, and some very cool paleontologist segments, not to mention CGI sequences that lasted more than 3 seconds apiece.

First, to call Spinosaurus little-known is a bit of a reach, isn't it? The narrator started nearly every post-commercial break segment with a line like "The most terrifying dinosaur you've never heard of." Yeah, Jurassic Park III wasn't as popular as the first film, but isn't Spinosaurus at least among Brachiosaurus in the ranks of well-known second-tier dinosaur stars nowadays? Or is it only among us dino fanboys? But who else is watching this show?

The next thing that struck me was the design of the CGI Spinosaurus. It is pretty darn inaccurate by today's standards. But... it isn't based on today's standards. It's clearly a direct copy of an older, very awesome drawing by Todd Marshall, down to the dewlap, the spikes, and the almost certainly inaccurate croc-like scale detailing. Whether Marshall was a consultant for the show, or they just ripped his design off after it turned up on Google Image Search, I don't know. Anybody know the scoop? Because if he wasn't involve, this is definitely a case of blatant plagiarism.

The main inaccuracy in their Spino model is the head. Now that we have decent skull material, we know Spino has a very narrow, thin snout with a distinct kink in the top and a huge rosette of teeth on the robust lower jaw (see accurate drawing, above). This is all thanks to dal Sasso and his team, who were featured extensively in the special (very cool to see) along with a life-sized model of an accurate skull. Does nobody notice the difference? Adding to the confusion, the special also featured segments with Lawrence Witmer in his famous anatomy lab (and Dr. Holtz's segments even super-imposed him into the lab via green screen, according to his comments on the DML!) . Witmer was shown using computer modeling to re-construct Spino based on the type specimens (destroyed in WWII) and with gaps filled in from the related Suchomimus. Unfortunately, the producers don't seem to have realized that the skull Witmer used was a stand-in, and anytime the skull of Spinosaurus was discussed (that is, every 2 minutes), the (very different) skull of Suchomimus was shown. Suchomimus skull also matches the one Marshall probably based his drawing on, so the accurate, dal Sasso restoration as briefly shown ends up looking very out of place.

Also bizarrely, the (almost universally accepted) idea that Spinosaurus was primarily a fisher is only addressed briefly at the very end, along with the hypothesis that the sail could be used as a fish-luring shade as in modern herons. The rest of the time, the talking heads like Holtz discuss ways Spino may have dispatched their prey, probably thinking of fish and small/juvenile dinosaurs and other vertebrates, while the animation shows it picking up and eating a small Rugops like corn on the cob! Never mind that the hand articulation would make corn eating impossible for theropod dinosaurs.

The commentary throughout the episode is actually very good, and mostly accurate, as it's coming from the pros, which are given more talk time than in some other specials. However, the animation and narrator talking about how bad-ass the Spinosaurus is are clearly meant to make it look like a bigger, meaner version of t. rex, rather than a giant heron. Don't get me wrong, giant herons would be damn scary, but I doubt they'd be running around eating abelisaur shish kebab and gutting giant mesoeucrocodylians like fish (very gory and kinda cool, don't see that in a lot of docs!). Also, there was a lot of speculation treated as fact. The bite and feeding style of Spinosaurus is based on modern crocodiles, by experts, but it's just speculation, not the basis of studies, and I've already seen people trying to add this to Wikipedia in the mistaken belief that it's been demonstrated scientifically. It's not even really a well-reasoned speculation, as the snout of Spinosaurus itself is more like a gharial than a crocodile. But maybe the expert quoted was thinking of the broader- snouted Suchomimus.

All in all, an interesting, schizophrenic doc, and I'm really looking forward to the Acrocanthosaurus installment, as that's known from much better remains, not to mention footprint evidence of hunting behavior. However, Discovery needs to get the experts to help write those commercial break trivia questions, and provide pronunciation guides--the poor guy kept calling it SPIN-o-saur-us, as in the Spin Doctors.

Oh, and this is two in a row that got the sauropod feet (nearly) right! The show featured Paralatitan, and you could clearly make the hands out as fingerless stumps. SV-POW must be having some effect!

The "lesser known" conceit was the first in some bizarre choices, pseudo-errors, and misleading narration/imagery to come from this special. Altogether, I can't say it was "better" than CotD, but to me it was heaps more interesting because of all these little quirks, and some very cool paleontologist segments, not to mention CGI sequences that lasted more than 3 seconds apiece.

First, to call Spinosaurus little-known is a bit of a reach, isn't it? The narrator started nearly every post-commercial break segment with a line like "The most terrifying dinosaur you've never heard of." Yeah, Jurassic Park III wasn't as popular as the first film, but isn't Spinosaurus at least among Brachiosaurus in the ranks of well-known second-tier dinosaur stars nowadays? Or is it only among us dino fanboys? But who else is watching this show?

The next thing that struck me was the design of the CGI Spinosaurus. It is pretty darn inaccurate by today's standards. But... it isn't based on today's standards. It's clearly a direct copy of an older, very awesome drawing by Todd Marshall, down to the dewlap, the spikes, and the almost certainly inaccurate croc-like scale detailing. Whether Marshall was a consultant for the show, or they just ripped his design off after it turned up on Google Image Search, I don't know. Anybody know the scoop? Because if he wasn't involve, this is definitely a case of blatant plagiarism.

Above right: Spinosaurus by Todd Marshall, blatantly plagiarized by me from Google Images. Left: Spinosaurus from Monsters Resurrected.

The main inaccuracy in their Spino model is the head. Now that we have decent skull material, we know Spino has a very narrow, thin snout with a distinct kink in the top and a huge rosette of teeth on the robust lower jaw (see accurate drawing, above). This is all thanks to dal Sasso and his team, who were featured extensively in the special (very cool to see) along with a life-sized model of an accurate skull. Does nobody notice the difference? Adding to the confusion, the special also featured segments with Lawrence Witmer in his famous anatomy lab (and Dr. Holtz's segments even super-imposed him into the lab via green screen, according to his comments on the DML!) . Witmer was shown using computer modeling to re-construct Spino based on the type specimens (destroyed in WWII) and with gaps filled in from the related Suchomimus. Unfortunately, the producers don't seem to have realized that the skull Witmer used was a stand-in, and anytime the skull of Spinosaurus was discussed (that is, every 2 minutes), the (very different) skull of Suchomimus was shown. Suchomimus skull also matches the one Marshall probably based his drawing on, so the accurate, dal Sasso restoration as briefly shown ends up looking very out of place.

Also bizarrely, the (almost universally accepted) idea that Spinosaurus was primarily a fisher is only addressed briefly at the very end, along with the hypothesis that the sail could be used as a fish-luring shade as in modern herons. The rest of the time, the talking heads like Holtz discuss ways Spino may have dispatched their prey, probably thinking of fish and small/juvenile dinosaurs and other vertebrates, while the animation shows it picking up and eating a small Rugops like corn on the cob! Never mind that the hand articulation would make corn eating impossible for theropod dinosaurs.

The commentary throughout the episode is actually very good, and mostly accurate, as it's coming from the pros, which are given more talk time than in some other specials. However, the animation and narrator talking about how bad-ass the Spinosaurus is are clearly meant to make it look like a bigger, meaner version of t. rex, rather than a giant heron. Don't get me wrong, giant herons would be damn scary, but I doubt they'd be running around eating abelisaur shish kebab and gutting giant mesoeucrocodylians like fish (very gory and kinda cool, don't see that in a lot of docs!). Also, there was a lot of speculation treated as fact. The bite and feeding style of Spinosaurus is based on modern crocodiles, by experts, but it's just speculation, not the basis of studies, and I've already seen people trying to add this to Wikipedia in the mistaken belief that it's been demonstrated scientifically. It's not even really a well-reasoned speculation, as the snout of Spinosaurus itself is more like a gharial than a crocodile. But maybe the expert quoted was thinking of the broader- snouted Suchomimus.

All in all, an interesting, schizophrenic doc, and I'm really looking forward to the Acrocanthosaurus installment, as that's known from much better remains, not to mention footprint evidence of hunting behavior. However, Discovery needs to get the experts to help write those commercial break trivia questions, and provide pronunciation guides--the poor guy kept calling it SPIN-o-saur-us, as in the Spin Doctors.

Oh, and this is two in a row that got the sauropod feet (nearly) right! The show featured Paralatitan, and you could clearly make the hands out as fingerless stumps. SV-POW must be having some effect!

Monday, December 7, 2009

Dinosaur Sunday: Good + Bad + Ugly

Last night, the first part of a new Discovery Sunday special aired, Clash of the Dinosaurs--sort of a slightly more rigorous and scientific-sounding version of the horrible Jurassic Fight Club. Hopefully, any DinoGoss fans will know that these types of CGI action-fests are only loosely connected to reality. One of the main criticisms of these shows, often pointed out online by the very experts featured as "talking heads," is that the writer will latch onto any speculative aside a scientist might have tossed around, and then present it in the show as a concrete fact. Apparently, audiences don't want to know about the process of science or that there may be debate (or no solid evidence at all) for some of these hypotheses. It's more exciting if we just know, man!

Anyway, in this post I'll go over a few things I noticed watching the show, informed by chatter on the DML today from some of he scientists featured and what they thought of the show. I'll also talk about the (very cool if very inaccurate in some very weird ways) show that followed (which I hadn't heard about!) all about Spinosaurus.

First, Clash of the Dinosaurs:

This species tried a bit harder than others to illustrate why we think dinosaurs were the way they're portrayed based on anatomical studies. Each CGI model came with a see-through version to show off the bones, muscles, gastric system, etc. While not perfect, they looked ok, though the show seemed to only focus on the brain for most dinosaurs. It also missed a good opportunity to highlight little-known aspects of anatomy, like the air sac system (especially in the sauropod and pterosaur).

External anatomy was even better in most cases. The T. rex looked great, much better than the god-awful Walking With Dinosaurs or slightly less awful Jurassic Park versions. The sub-adult Triceratops were cool looking despite the extra front foot claw, and from what we saw of the ankylosaur, they obviously did their research (hey, Ken Carpenter was one of the talking heads) rather than just giving it a random arrangement of nodes and scutes. The Quetzalcoatlus was decent, about on par with the When Dinosaurs Roamed America version, but it was not only naked but scaly, a complete departure from known science. Nice to see the leapfrog launch and terrestrial stalking papers come to life. However, the wings looked too much like simple flaps of skin, as in a bat. And the "X-rays" and narration gave no indication that they were anything but skin. No mention of the complex system of muscluature, inflatable sacs, etc. that made these structures true organs, rather than dermis.

The discussion of Quetz's eyesight is a good spot to illustrate one of the points I mentioned above. The show asserted that Quet could see in UV, following urine trails etc. of its prey on the ground, and that it would have been eagle-eyed, hunting mainly from the air. The reason all this was in the show, is that expert Mike Habib (one of the talking heads) had a quick back and forth with the interviewers, who asked him if its eyesight would be as good as birds. Mike said it was plausible that it would have had similar eyesight to storks and hawks, and that (since it apparently hunted prey on the ground) maybe could have spotted food from the wing. This translated to Terminator-vision and rock-solid factual statements that it could see for miles. Of course, we have no way of knowing, but I would have said that it would be more stork-like than eagle-like, hunting on the ground, not on the wing.

The sauropod segments were especially good, and the show obviously benefited from having Matt Wedel of SV-POW! as a talking head. It did a good job explaining the age segregation of juveniles, and their "flood out the predators with food" reproductive strategy. Even the CGI models of Sauroposeidon were very good, with the correct number of fingers (though the back of the front feet were still elephantine and not concave as they should have been, but they're trying!).

What I can't forgive is the Deinonyhcus models, which while better than usual (certainly leagues better than JFC) still looked like ugly, overgrown lizards rolled in glue with feathers slapped on willy-nilly, very unnatural, with artificially "mean" looking faces (and apparently, Joker makeup for that extra serial-killer punch). The wing feathers were barely visible, and for a while I thought the arms were naked. What's the point of retaining wings for display (as we know for a fact medium-sized dromaeosaurs did) if you can barely see them? Basically, while CGI animators are getting better at following the facts (raptors had feathers), they're not getting the implication (they should look like giant Archaeopteryx, not mini T. rex with fuzz).

Summing it all up is an excellent quote from Tom Holtz (also featured on the show):

"The documentarians often take anything that any of the talking heads speculated about, and transformed these into declarative statements of fact. In some cases this is particularly egregious, because I strongly disagree with some of these statements and believe the facts are against some of these (say, about tyrannosaurid cranial kinesis...) and they present these as facts rather than suppositions."

For the record, on that cranial kinesis point, dinosaurs could NOT flex their jaws open like pythons. Lawrence Witmer, another consultant on the show, has demonstrated this thoroughly in print, but was not given a say on the matter, which is especially bad since it implies all the experts agree with Dr. Bob on this. Really, I imagine the producers must have loved having Bakker as a talking head, since it gave them license to depict all kinds of zany speculation as fact. I owe a lot to Bakker and idolized him as a kid, but I'd hesitate to call what he does 'science' and not 'unsubstantiated speculation to hype science for kids.'

One last pet peeve, then stay tuned for Spino. I'd estimate the CGI segments of the show totalled about 5 minutes of footage, with clips repeated over and over and over and over again to illustrate different points. I'd gladly accept lower-quality CGI if we could at least get some actual 'action' sequences that last more than 5 seconds apiece, and it makes me wish they'd bring back cheaper methods, even stop-motion. Some of the pieces showed even more skimping, like the baby Sauroposeidon with Walking With... Dimetrodon syndrome. That is, the hatchlings use the same model as the adults, making it look like they shrunk down, Mario style. Even worse, the Sauroposeidon hatching sequence takes place at night, on a wide sandy featureless field. With no sense of scale, it looks a herd of adult brachiosaurs emerging from the soil on the moon, which is actually pretty cool.

Oh well. At least they didn't put a Suchomimus head on their T. rex, but more on that later...

Friday, October 30, 2009

Toro! Toro! Toro!

By now, all dino fans have probably heard the buzz on the indicator: Jack Horner and team are working on a paper which attempts to prove that Torosaurus and Triceratops are the same thing, and that in general, growth series in dinosaurs are often misinterpreted as numerous similar species (something that has long been acknowledged in pterosaurs and recently in early birds like Archaeopteryx and, probably, Confuciusornis).

Here's the quick and dirty background: Triceratops was named by O.C. Marsh in 1889 based on a pair of horns and skull roof collected in 1887 from Colorado. Numerous complete specimens followed, making Triceratops the archetypal horned dinosaur with its two long forward-pointing brow horns and single short, forward-pointing nose horn, in front of a relatively short (by ceratopsian standards), solid frill. The frill is notable: most ceratopsians, including close relatives of Triceratops, have long frills with large openings, or fenestrae, in the bone.

Torosaurus was described a few years later in 1891, also by Marsh, based on two skulls. Unlike Triceratops, the Torosaurus skulls had long frills with the standard fenestrae. Its frill was also smooth around the edges: many Triceratops specimens show that they had small, bony scutes adorning the frill's edge, called epoccipitals.

According to Horner's talks at SVP, which he also summarized in an interview on the podcast The Skeptic's Guide to the Universe (available here), those differences are not due to species variation, or even sexual dimorphism as previously hinted. Rather, Torosaurus is nothing more than the most mature growth stage of Triceratops. The paper isn't out yet so all the data isn't available, but presumably Horner will demonstrate based on microscopic bone growth studies that all the specimens currently assigned to Triceratops are not fully mature, and that like modern birds, some secondary sexual characteristics (such as the expanded, chasm-filled frill) pop up quite suddenly at the 'last minute' in the animal's growth, after it has already reached nearly adult size.

We can already see heaps of major changes taking place as Triceratops grows. Juveniles have backward curving horns, which completely change to point forward during growth. Remember those epoccipital fringes, the lack of which is so diagnostic of Torosaurus? We already see them becoming reduced from tall, pointed osteoderms in younger forms to smooth and rounded, and finally merging with the frill itself and smoothing out so as to be almost invisible. Indeed, in these oldest individuals, the bone in the center of the frill can also be seen to thin like a man's receding hairline. Given that we already know all of this about Trike's growth, it's not a very huge leap to recognize a long, smooth, holy frill as the next logical step, and those just happen to have been named Torosaurus for 110 years.

The goss has been flying over this online, and a few interesting tidbits have come up. Having grown up in the Northeast US, the most interesting to me concerns the mistaken identity of some specimens of Triceratops. For me, the quintessential Triceratops is the one in the American Museum of Natural History (specimen AMNH 5116). However, as many have pointed out on DinoForum and elsewhere, it's also among the most... well, un-Triceratops like.

Above: Triceratops skull 'classic' vs. specimen AMNH 5116. By Ed T. and Michael Gray (right), licensed.

Above: Triceratops skull 'classic' vs. specimen AMNH 5116. By Ed T. and Michael Gray (right), licensed.Compare the images above. On the right is my beloved AMNH Trike. On the left is a 'classic' Triceratops skull. The frill on the AMNH specimen is longer, and lacks epoccipitals. The frill is also tall and back-swept, not flared out to the sides, as in most Triceratops skulls. Not only that, but as you can see in the image at the top of this post (which is a more contrasty view of the same AMNH skull), almost all of the frill has been restored in plaster to conform with what a Trike should look like. There are significant gaps in the middle of the frill entirely filled with plaster... exactly where the fenestrae of Torosaurus go. If Torosaurus and Triceratops are indeed separate species, the AMNH Trike is no Trike at all... it's a Torosaurus in disguise!

Thankfully, it's more than likely that there is no such thing as Torosaurus, any more than there was a Brontosaurus. It's all Triceratops baby, and we can conclude that this famous last of the ceratopsians was indeed last, the only one of its kind in the Lance and Hell Creek Formations that date to the very end of the Mesozoic era.

But... wait... isn't there another named ceratopsian from the same time and place? Named BEFORE Triceratops?? If there was only one Lance/Hell Creek ceratopsian, then Torosaurus get sunk into Triceratops as a synonyms. Does Triceratops then have to be abandoned in favor of... Agathaumas!?

Dun dun duuuuuun!

Friday, October 16, 2009

Meet the Megaraptors

Above: Illustration of the megaraptoran Australovenator by T. Tischler, licensed.

Well, that all came together...The history of Megaraptor is long and sordid. It was first described as a gigantic dromaeosaurid (hence the name), on the basis of a large sickle-claw found in Argentina. In fact, I remember a time when rumors circulated that the newly described Unenlagia might turn out to be a juvenile form Ironically, an ACTUAL gigantic unenlagiine dromaeosaurid from almost the same time and place was later found, in the form of Austroraptor. Not to be confused with Austrovenator, which, see below...

Then, a complete Megaraptor forelimb was found that crushed the dreams of every 12 year old Jurassic Park fanboy who had already adopted Megaraptor as their personal mascot: The giant claw came from the hand, not the foot, and it was no raptor at all: but what was it? The first thing that comes to mind is the similar story of Baryonyx ("heavy claw"), named for a similar giant claw that was similarly thought to come from the foot of a dromaeosaur, and similarly later found to come from the hand (have we learned nothing?). Baryonyx was actually a spinosaur, and the large hand claw seemed to be a unique feature of that group. So, was Megaraptor a spinosaur? Opinion was divided for years, with Megaraptor being placed either among the spinosaurs, the carcharodontosaurids*, or in some weird, new family of tetanuran theropods.

Above: Replica of a Megaraptor claw. Photo by Haplochromis, licensed.

Above: Replica of a Megaraptor claw. Photo by Haplochromis, licensed.The picture got clearer with a few discoveries in just the past year from 'Stralia. First, a large claw that looked suspiciously like the hand claw of Megaraptor, followed by a more complete specimen of a similar animal, named Australovenator. Australovenator looked like a good cantidate for a Megaraptor relative, and studies showed it was in fact an allosaur, somewhere between Allosaurus and carcharodontosaurids.

Well, a new study online today helps clarify the situation a whole lot. Benson, Carrano and Brusatte ran a massive phylogenetic analysis of allosauroids, and recovered a monophyletic clade that happens to include almost every oddball misfit theropod in the book. Called Neovenatoridae, this new clade includes the titular Neovenator (at times thought to be an advanced allosaurid or primitive carcharodontosaurid) and the enigmatic Chilantaisaurus, also previously thought to be a spinosaur. Neovenatorids more advanced than those two are placed in the advanced unranked clade Megaraptora (a nice compliment to the dromaeosaurid clade Microraptoria), which includes Megaraptor and Australovenator as well as perennial phylogenetic stragglers Aeroseon, Fukuiraptor and Orkoraptor. This true identity for Orkoraptor (previously thought to be a coelurosaur) is particularly interesting, since it lived so recently--only 70 million years ago, close to the end of the Mesozoic, showing that derived allosaurs lived right to the end, rather than dieing out in the mid-Cretaceous as previously thought.

All in all, this new paper is pretty major. It reveals a new clade of theropods of a type not really known before, even though none of the constituent species is actually new. What all the megaraptors have in common is a light, gracile build with often hollow bones (seen in the extreme case of Aerosteon), relatively long front and hind limbs (indicating a fast-running lifestyle) and large, hooked claws on the hands for grappling prey. Basically, this advanced line of "coelurosaur mimicking" allosaurs survived in the southern hemisphere while coelurosaurian carnivores were dominating the northern continents, during and after the time of their traditionally carnosaurian relatives carcharodontosaurids.

* I had to stop myself from writing "carcharodontosaurian" instead of "-id" a few times. See, neovenatorids and carcharodontosaurids are sister groups, and the clade containing both has been named Carcharodontosauria. So, technically, Megaraptor is a carcharodontosaur after all, just not a carcharodontosaurid proper.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

The Near-Bird Cometh

Above: New specimen of Anchiornis and skeletal showing feather proportions, from Hu et al. 2009. Click to embiggen.

Above: New specimen of Anchiornis and skeletal showing feather proportions, from Hu et al. 2009. Click to embiggen.Being a protobird fan myself, this prompted me to immediately go to the nature.com online preprint section and start clicking refresh faster than you can whip a ram at Brewfest. Needless to say I was dissapointed and will have to start hounding J. about the paper until something pops up on the DML to whet my appetite for photos so I can get started drawing this thing. More to come one I have a chance to read the paper and collect some goss!

UPDATE:

Just been informed that not only is this on Nature's front page, but the pdf appears to be free? Or is it because I'm logged in?

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Raptorex update

Quick taxonomic update: Having just gotten the paper, I can comment that Bill Parker's concerns over the name Raptorex kriegsteini (see previous post), echoed on the DML, are based on misrepresentation of the issue by the newspaper reports. At least one news story said that Kriegstein named the species after his parents, so by ICZN rules the species name needs to be R. kriegsteinorum (-orum being the correct suffix for a name honoring multiple people). However, the paper explicitly states that the species is named only for Roman Kriegstein, so the current name is correct. For the record, here's the entire etymology section from Sereno et al. 2009:

Etymology: raptor, plunderer (Greek); rex, king (Greek); kriegsteini, after Roman Kriegstein, in whose honor the specimen was secured for scientific study.

Also, the paper makes clear that, unlike I speculated before, Guanlong, Dilong and friends are still recovered as tyrannosauroids in the paper's cladogram, though more basal than Raptorex.

Also, the paper makes clear that, unlike I speculated before, Guanlong, Dilong and friends are still recovered as tyrannosauroids in the paper's cladogram, though more basal than Raptorex.

Raptorex. For serious, that's a real dinosaur now.

Above: Paul Sereno with a model and skull cast of Raptorex, possibly the most ridiculously named dinosaur of all time. Photo from Chicago Tribune by Nancy Stone.

Above: Paul Sereno with a model and skull cast of Raptorex, possibly the most ridiculously named dinosaur of all time. Photo from Chicago Tribune by Nancy Stone.Headline: DeviantArtist Honoured with Dinosaur Name

Well not really, but surely raptorex must be stoked that his (let's face it), fun but pretty ridiculous username is now the name of a real life dinosaur, Raptorex kriegsteini.

The mini-tyrannosaur is from the Yixian ash beds (not the more famous lake sediments that preserve feathers), and is a bit improbable in other ways than its name. It looks like a mini-Tarbosaurus, with short, two-fingered hands and long, running legs, all things expected from a juvenile tyrannosaurid, rather than a (supposed) primitive tyrannosauroid like Dilong or Guanlong. I wonder if this has implications for their position as basal tyrannosaurs--the paper, supposedly released in the online edition of Science today, is nowhere to be found, for my part.

Raptorex also has a sordid past. Apparently, the fossil was smuggled out of China and sold at (where else) the Tuscon fossil show to a private collector for tens of thousands of dollars. The collector, ophthalmologist Henry Kriegstein (whose family name is honored in the specific name of the new dino), had specialists in Utah prep it out of its matrix so he could mount it in his Massachusetts living room. Upon discovering the specimen was not a juvi tarb as advertised, but rather a full-grown individual, Paul Sereno (so that explains the name!) was called in for further advice, and recognized it as an important discovery. Kriegstein soon agreed to relinquish his purchase to science (with a bonus in the form of naming rights, of course. At least he wasn't a big Bambi fan).

In a bit of taxonomic goss, Bill Parker over at Chinleana notes that, as Kriegstein technically named the genus for his parents, not himself (which is frowned upon), the ICZN mandates that the species name needs to be emended to kriegsteinorum, so watch for that change in the future, likely published by George Olshevsky or a similar stickler for proper Latin.

And, of course, Jack Horner has weighed in. In an email to Wired.com, Horner explained that he thinks the small, fleet-footed Raptorex, because it has the same body plan as larger tyrannosaurs, somehow proves that tyrannosaurs evolved into pure scavengers early on, and that the authors are jumping to conclusions in thinking that long, speed-designed legs somehow imply "predator." Keep on keepin' on, Horner.

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Oh Giraffatitan, where art thou?

Above: Skull of Brachiosaurus altithorax (right, from Carpenter & Tidwell, 1998) and "B." brancai (left, by Gunner Rias, licensed).

Above: Skull of Brachiosaurus altithorax (right, from Carpenter & Tidwell, 1998) and "B." brancai (left, by Gunner Rias, licensed). A curious bit of goss, and potential drama?, teased out Mike Taylor and crew at SV-POW.

In recent posts about a new brachiosaurid announced last week, Qiaowanlong (or is it a brachiosaurid? See SV-POW for in-depth coverage), Mike Taylor consistently reffers to the genus "Brachiosaurus" brancai.

The goss stems form use of the quotes. As we all know, when discussing scientific names, the genus and species are always put in italics. The exception to this are nomina nuda, which are names not properly described or coined. Another exception is when a genus and species combo is found to be invalid for whatever reason. For example, the name Ingenia, for an oviraptorid, is preoccupied and has not yet been renamed. But the species name yanshini is still valid. So, when we talk about this species, we might write it as "Ingenia" yanshini to indicate that the genus name is going to change.

Similarly, this same notation is used for species previously assigned to one genus but are no longer considered related to that genus' type, and are pending reclassification under a new genus name. For example, the species "Dilophosaurus" sinensis is probably not closely related to Dilophosaurus wetherilli, so it gets quotes until a replacement name is chosen. This is also the current situation with "Brachiosaurus" brancai. Many people have suspected that this African sauropod is not the closest relative of the North american type species, Brachiosaurus altithorax, given that a B. altithorax skull has been identified that differs from the African species (see photos above), among other differences in skeletal shape and proportion.

So what's wrong with using quotes when talking about "B." brancai? The African version has already been given a new name! In a 1988 paper, Greg Paul coined the name Giraffatitan for a distinct "subgenus" containing the African species. This was later formalized as a genus name, I believe by Olshevsky in his Mesozoic Meanderings, but correct me if I'm wrong.

So wy write "Brachiosaurus" brancai when, if considering this a separate genus, it should rightly be Giraffatitan brancai? I asked Mike about it, and apparently a paper explaining will be coming out in a week or so. The goss at SV-POW for quite some time has been that the SV-POWsketeers favor a separate genus for "B." brancai, but the assumption was always that this would be Giraffatitan. Mike is playing coy for now--is it simply that the authors don't like the name Giraffatitan? Mike says this is the only paper he's seen in which the acknowledgments contain an apology, so it sure sounds like that is close to the truth...

But a valid name can't be rejected simply because an author doesn't like the sound of it. It would have to be argued away on technical grounds. Is the fact that Giraffatitan was originally a subgenus, not a proper genus, coming into play and allowing Giraffatitan to be re-named? Is the apology directed towards George Olshevsky (maybe the authors don't consider his self-publications valid?). I don't know the ins and outs of priority when it comes to subgenera and subspecies. But we'll know shortly...

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

The Colour and the Shape

Above: Iridescent Peacock feather, from Flickr. A new study shows that patterns, iridescence and even color can be preserved in fossil feathers.

Above: Iridescent Peacock feather, from Flickr. A new study shows that patterns, iridescence and even color can be preserved in fossil feathers.Every dinosaur picture book aimed at kids comes with a disclaimer /slash/ incentive: "We don't really know what colors dinosaurs were." They were often depicted as green and drab, camouflage suited to their 1930s-era stint as lethargic reptilian swamp dwellers. But, the kid's books tantalizingly continue, "they could have been any color, with any pattern, even bright fuscha with purple polka dots!" (I'm guessing these books are to blame for Barney...).

Well, that's mostly true. We now know dinosaurs are more closely related to birds than modern reptiles (and lets not sell those short, many are very brightly colored). Birds have excellent color vision, and often employ bright colors and striking patterns to attract mates. Some artists have taken this concept to the extreme: See the almost day-glo colors employed by Luis Rey. All of this falls within artistic license, though even this bastion of dinosaur mysteries may disappear for some species. Actually, color can be preserved in fossils, and several recent studies have applied this to fossilized feathers, like those found on some dinosaurs.

Above: One of the iridescent feathers studied by Prum and colleagues in the new paper, discussed below. From National Geographic.

Above: One of the iridescent feathers studied by Prum and colleagues in the new paper, discussed below. From National Geographic.Fossils preserving life body patterns or even color are not new. Many fossilized fish and insects have preserved patterning or even hints of iridescence in their wings, shells, and scales. At least one ammonite fossil is even said to preserve the original, blood red coloration, possibly indicating a deep-sea habitat due to similar color in modern animals from that environment.

A new technique has been developed to help determine if color patterns are real or due to preservation. A 2008 paper by Jakob Vinther and colleagues described looking at apparently patterned fossil feathers under a microscope, looking for (and finding) melanosomes, the remnants of pigment present in life. The traditional view held that most fossil feathers which are preserved as dark 'stains' in a halo around the fossil are caused by bacteria, which cover the feathers as they decay. Vinther and colleagues found fault with that interpretation, though. For example, some fossil feathers show both dark and light bands in regular patterns. Why would bacteria only be present in such regular segments of fossil feathers? Vinther reckoned that rather than bacteria, the small nodules associated with these bands and dark spots (seen under a microscope) were pigment cells, and represented the actual dark/light patterning (though not the specific color) that would have been present in the living animal. Vinther and colleagues concluded that in fact almost all fossil feathers are preserved this way.

That's not to say that feathers lacking a dark carbon film lacked melanin in life--further examination is needed. For example, most specimens of Archaeopteryx do not preserve dark, stained feather impressions. Does this mean the feathers were white? No--in fact, close examination shows impressions where melanosomes would have been, but have since been lost or decayed away.

Still, this could have implications for the famous feathered dinosaur fossils from China. Many of these do preserve feathers as dark carbon stains (presumably caused in part by melanin), and do sometimes show a banded pattern. Such banding can be seen in the tail feathers of Caudipteryx. The "ring tailed" appearance of the holotype Sinosauropteryx tail is probably real, given an unpublished study by Nick Longrich and confirmation (via Dinoforum, of course) that the bands match up across both fossil slabs and so can't be an artifact of splitting the rock as originally suggested. Longrich also suggested that the apparent absence of feathers on the underside of Sinosauropteryx doesn't mean they weren't there, but rather that these feathers were white and did not leave a stain in the rock. Whether or not these feather patterns contain melanin is still an open question that, to my knowledge, nobody has really studied.

Above: Sinosauropteryx may have been counter-shaded, with a white belly and ringed tail. Image from a work in progress digital painting by Matt Martyniuk, all rights reserved.

Above: Sinosauropteryx may have been counter-shaded, with a white belly and ringed tail. Image from a work in progress digital painting by Matt Martyniuk, all rights reserved.So, we might actually know what kinds of patterns a few dinosaurs had in life, thanks to preservation of feathers and melanin. But what about actual colors? Well, a new study of melanin in fossil feathers (this time from the Eocene Messel deposits of Germany, home of Darwinius) has found that even traces of iridescence and life color can be recovered. In the future, more detailed study of dinosaur feathers might reveal something similar. A few barely-published specimens of Microraptor do have a very beautiful blue sheen to them (see photo above). Preservation artifact, or dromaeosaurid Blue Jays?

Luckily, formal evaluation of the feathered dinosaurs using this technique is in the pipeline. As co-author of the study Richard Prum told NatGeo, "We are eagerly hoping to be able to work on some of the Chinese dinosaur feathers to try to reconstruct the colors of the feathered dinosaurs." So, the days of drawing these dinosaurs with whatever day-glo magenta stripes you like may be over.

Above: Tail feathers of Microraptor specimen TNP0099624, from figure 2 in Xu et al. 2003. Could these show the color in life or iridescence? Future studies will find out.

Above: Tail feathers of Microraptor specimen TNP0099624, from figure 2 in Xu et al. 2003. Could these show the color in life or iridescence? Future studies will find out.And does anybody else remember that very old bit of goss from the DML about a Velociraptor specimen with associated feather proteins that could reveal the color...?

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

PteroGoss

Nothing much to report in the way of good goss lately. It's been quiet in the world of dinosaurology... almost too quiet...

But not so if you're also a big pterodactyl geek. This is not PteroGoss but I'll link to a few awesome stories coming out lately...

Eudimorphodon rosenfeldi has been assigned to a new genus, Carniadactylus, in a sweet paper looking at relationships of primitive pterosaurs. The authors also consider the super-weird Raeticodactylus to actually be a synonym of the contemporary Caviramus. Here's the article from Wikipedia.

Mark Witton describes a new species of Tupuxuara, T. deliradamus! That translates as "crazy diamond," making it officially one of the most awesome pterosaur names that could also be a character in a Guy Ritchie film. Mark also sorted out the priority of Tupuxuaridae vs Thalassodromidae, which you can read about at his blog.

In other Mark Witton news, he's the subject of a new series of videos done by the BBC tracking the construction of several giant pterosaur models for an upcoming British exhibition. Check out TetZoo for more.

Above: Sketch of the upcoming outdoor pterosaur models at the Southbank Centre in London, for the Royal Society exhibition. Copyright BBC.

Above: Sketch of the upcoming outdoor pterosaur models at the Southbank Centre in London, for the Royal Society exhibition. Copyright BBC.Tuesday, July 14, 2009

My Sauropod is Bigger

There is a new record holder for second-longest dinosaur, longest if you only count bones that currently exist. Skip past the long-winded intro if you want to get to the point!

New mounted skeleton of Mamenchisaurus, in Tokyo, the longest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world. Image by Shiziuo Kambayashi from the AP.

New mounted skeleton of Mamenchisaurus, in Tokyo, the longest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world. Image by Shiziuo Kambayashi from the AP.

What is it about pissing contests over the largest dinosaurs? Who cares if Spinosaurus is a few metres longer than Tyrannosaurus? Does it really matter which super long-necked, long tailed giant sauropod is slightly longer than its nearest competitor?

Of course it does!

Well not really, but it can be a fun part of armchair paleontology to keep track of these things. I created the Wikipedia article Dinosaur Size to try and help people keep tabs on this issue using peer-reviewed sources (though for a while there a few too many Internet sources were creeping in, but we've put a stop to that).

Now, everyone gets their shorts in a bunch over the biggest theropod, because even though sauropods are nearly always bigger, they're not the ones who will try to eat Jeff Goldblum. This is evidenced by the fact that one of the biggest theropods in terms of sheer mass, Therizinosaurus, is almost always ignored in these competitions because it was probably herbivorous and looked like a giant porcupine goose with a beer belly. However, despite how cool theropods may be (i.e., extremely cool), sauropods are without a doubt the group where we find the largest dinosaurs.

So which dinosaur was largest? Well, define large. Do you mean length, height, or mass? In modern animals, mass is usually what counts. The African elephant is considered the largest land animal, even though the giraffe is taller and the reticulated python is longer. The most massive, and therefore largest, dinosaur known from decent remains that still exist is a bit of a tie game right now. Traditionally, the largest sauropod known is cited as the titanosaur Argentinosaurus, with rational mass estimates ranging between 78 and 83 tonnes. However, several other titanosaurs were about the same size, if not bigger, including Puertasaurus and the horrifically named Futalognkosaurus (note that the official name even includes a misspelling, yikes!).

Scale diagram showing several of the largest dinosaurs discussed in this post. Green: Diplodocus. Orange: Supersaurus. Purple: Argentinosaurus. Blue: Sauroposeidon. Grey: Bruhathkayosaurus. Red: Amphicoelias. Scale bar = 40m. Image by Matt Martyniuk, licensed.

The new goss here though, to finally get to the reason for this post, is that the record for longest dinosaur has changed... sort of (see final paragraph, below). When I was a kid, I was enthralled by the longest known dinosaur according to several of my books, the "Seismosaurus" (earthquake lizard). This monster diplodocid (whip-tailed sauropod) was said to be over 130ft in length. Well, those initial estimates were a little too hopeful, and based on the mis-identification of a tail bone which threw the estimates off by up to 30%. More reasonable estimates place its total length at a mere 33.5m (110ft), and furthermore, it turned out to likely be just a slightly oversize specimen of Diplodocus anyway.

The downsizing of Seismo--er, Diplodocus left the length champion to its cousin, Supersaurus. As the preparation of a fairly complete skeleton nicknamed "Jimbo" by Scott Hartman showed, Supersaurus probably reached a total length of 34m, or 112ft, surpassing both Diplodocus and weight champion Argentinosaurus by a meter or two (in the process robbing the titanosaurs of their clear victory in both units of measure).

However, now a new champion emerges by a neck (I'll be here all weekend folks!). A new specimen of the mega-necked Chinese sauropod Mamenchisaurus unearthed in 2001 was initially reported as the largest of its kind at a respectable, but short, 30m (98ft). However, a surprise came when they assembled a reconstructed skeleton for a new exhibition opening in Tokyo: the specimen actually measures a whopping 35m long, or 115ft, beating out Supersaurus for the title of longest known dinosaur. See photo at top of this post.

Extraordinarily accurate (down to the scales) illustration on Mamenchisaurus by Steve OC, licensed.

Extraordinarily accurate (down to the scales) illustration on Mamenchisaurus by Steve OC, licensed.

That is, if you don't count Amphicoelias. This monster, known from a single partial vertebrae that was 8ft tall and would have been 12 if complete, was very similar to Diplodocus and, scaling up from the same bone in that animal, Amphi would have been at the very least 40m long (131ft) and probably in the area of 120 tons, easily trumping all other contenders in every category: length, weight, and height (read the Wiki I started and wrote most of on Amphi here). So far the only contender to that throne is the even more dubious Bruhathkayosaurus, which is known from a poorly preserved, poorly published, and basically never studied leg bone sometimes thought to be a tree trunk, and even if the size the describers said it was is probably vastly overestimated in published surveys. For now, Amphi is the king, but its smaller cousins with better remains are inching closer.

New mounted skeleton of Mamenchisaurus, in Tokyo, the longest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world. Image by Shiziuo Kambayashi from the AP.

New mounted skeleton of Mamenchisaurus, in Tokyo, the longest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world. Image by Shiziuo Kambayashi from the AP.What is it about pissing contests over the largest dinosaurs? Who cares if Spinosaurus is a few metres longer than Tyrannosaurus? Does it really matter which super long-necked, long tailed giant sauropod is slightly longer than its nearest competitor?

Of course it does!

Well not really, but it can be a fun part of armchair paleontology to keep track of these things. I created the Wikipedia article Dinosaur Size to try and help people keep tabs on this issue using peer-reviewed sources (though for a while there a few too many Internet sources were creeping in, but we've put a stop to that).

Now, everyone gets their shorts in a bunch over the biggest theropod, because even though sauropods are nearly always bigger, they're not the ones who will try to eat Jeff Goldblum. This is evidenced by the fact that one of the biggest theropods in terms of sheer mass, Therizinosaurus, is almost always ignored in these competitions because it was probably herbivorous and looked like a giant porcupine goose with a beer belly. However, despite how cool theropods may be (i.e., extremely cool), sauropods are without a doubt the group where we find the largest dinosaurs.

So which dinosaur was largest? Well, define large. Do you mean length, height, or mass? In modern animals, mass is usually what counts. The African elephant is considered the largest land animal, even though the giraffe is taller and the reticulated python is longer. The most massive, and therefore largest, dinosaur known from decent remains that still exist is a bit of a tie game right now. Traditionally, the largest sauropod known is cited as the titanosaur Argentinosaurus, with rational mass estimates ranging between 78 and 83 tonnes. However, several other titanosaurs were about the same size, if not bigger, including Puertasaurus and the horrifically named Futalognkosaurus (note that the official name even includes a misspelling, yikes!).

Scale diagram showing several of the largest dinosaurs discussed in this post. Green: Diplodocus. Orange: Supersaurus. Purple: Argentinosaurus. Blue: Sauroposeidon. Grey: Bruhathkayosaurus. Red: Amphicoelias. Scale bar = 40m. Image by Matt Martyniuk, licensed.

The new goss here though, to finally get to the reason for this post, is that the record for longest dinosaur has changed... sort of (see final paragraph, below). When I was a kid, I was enthralled by the longest known dinosaur according to several of my books, the "Seismosaurus" (earthquake lizard). This monster diplodocid (whip-tailed sauropod) was said to be over 130ft in length. Well, those initial estimates were a little too hopeful, and based on the mis-identification of a tail bone which threw the estimates off by up to 30%. More reasonable estimates place its total length at a mere 33.5m (110ft), and furthermore, it turned out to likely be just a slightly oversize specimen of Diplodocus anyway.

The downsizing of Seismo--er, Diplodocus left the length champion to its cousin, Supersaurus. As the preparation of a fairly complete skeleton nicknamed "Jimbo" by Scott Hartman showed, Supersaurus probably reached a total length of 34m, or 112ft, surpassing both Diplodocus and weight champion Argentinosaurus by a meter or two (in the process robbing the titanosaurs of their clear victory in both units of measure).

However, now a new champion emerges by a neck (I'll be here all weekend folks!). A new specimen of the mega-necked Chinese sauropod Mamenchisaurus unearthed in 2001 was initially reported as the largest of its kind at a respectable, but short, 30m (98ft). However, a surprise came when they assembled a reconstructed skeleton for a new exhibition opening in Tokyo: the specimen actually measures a whopping 35m long, or 115ft, beating out Supersaurus for the title of longest known dinosaur. See photo at top of this post.

Extraordinarily accurate (down to the scales) illustration on Mamenchisaurus by Steve OC, licensed.

Extraordinarily accurate (down to the scales) illustration on Mamenchisaurus by Steve OC, licensed.That is, if you don't count Amphicoelias. This monster, known from a single partial vertebrae that was 8ft tall and would have been 12 if complete, was very similar to Diplodocus and, scaling up from the same bone in that animal, Amphi would have been at the very least 40m long (131ft) and probably in the area of 120 tons, easily trumping all other contenders in every category: length, weight, and height (read the Wiki I started and wrote most of on Amphi here). So far the only contender to that throne is the even more dubious Bruhathkayosaurus, which is known from a poorly preserved, poorly published, and basically never studied leg bone sometimes thought to be a tree trunk, and even if the size the describers said it was is probably vastly overestimated in published surveys. For now, Amphi is the king, but its smaller cousins with better remains are inching closer.

Wednesday, July 1, 2009

More On Chewy Hadrosaurs

First, thanks to those who commented and emailed regarding my post on the controversial hadrosaur chewing mechanics paper (see "Nom nom nom"). Vince Williams, lead author of the paper in question, was among those who contacted me about it, and he pointed out an error that stems from (yet again) science reporting that isn't all there.

Above: Underside of the skull of Leonardo, the Brachylophosaurus mummy. By Ed T., from Flikr. Licensed.

Above: Underside of the skull of Leonardo, the Brachylophosaurus mummy. By Ed T., from Flikr. Licensed.

My last post reiterated a statement from this MSNBC article, that gut contents of the famous hadrosaur mummy "Leonardo" seem to contradict Williams et al.'s findings, because the plant matter was

a) chopped or sheared, not chewed, and

b) mainly coniferous, indicating that hadrosaurs were browsers rather than grazers.

Well, I checked up on the source that MSNBC used for this information (Leonardo is, despite documentaries on the History Channel, not fully studied and published on yet). That lead me to another MSNBC article on Leo, which appears to state the opposite! From the older, cited article:

Above: Underside of the skull of Leonardo, the Brachylophosaurus mummy. By Ed T., from Flikr. Licensed.

Above: Underside of the skull of Leonardo, the Brachylophosaurus mummy. By Ed T., from Flikr. Licensed.My last post reiterated a statement from this MSNBC article, that gut contents of the famous hadrosaur mummy "Leonardo" seem to contradict Williams et al.'s findings, because the plant matter was

a) chopped or sheared, not chewed, and

b) mainly coniferous, indicating that hadrosaurs were browsers rather than grazers.

Well, I checked up on the source that MSNBC used for this information (Leonardo is, despite documentaries on the History Channel, not fully studied and published on yet). That lead me to another MSNBC article on Leo, which appears to state the opposite! From the older, cited article:

- "An analysis of the gut contents from an exceptionally well-preserved juvenile dinosaur fossil suggests that the hadrosaur's last meal included plenty of well-chewed leaves digested into tiny bits."

- "An analysis of pollen found in the specimen's gut region revealed a variety of plants, including ferns, conifers and flowering plants. Although the pollen could have been ingested when the dinosaur drank water, the tiny leaf bits, under 5 millimeters (a quarter-inch) in length, indicate that Leonardo was a big browser of plants, Chin said."