Showing posts with label pop culture. Show all posts

Showing posts with label pop culture. Show all posts

Sunday, June 10, 2018

Review: "Beasts of the Mesozoic" Tsaagan by Creative Beast Studios

Quick Facts

2018 Beasts of the Mesozoic Raptor Series Tsaagan mangas action figure

Size: 20cm long

Scale: 1:6

Sculpted by: David Silva

Produced by: Creative Beast Studios

Back in April 2016, toy industry veteran David Silva launched a Kickstarter campaign to produce scientifically accurate "raptor" (eudromaeosaur) figures. Unlike the vast majority of static PVC dinosaur figures on the market, these would be super articulated, with up to 24 joints allowing significant posability. Now, over two years later, the project has become a reality, and my selection of a Wave 2 Tsaagan mangas figure has finally arrived. So, how does it stack up to the high expectations and lofty claims that these are the most scientifically correct dinosaur action figures on the market?

Sunday, April 30, 2017

Review: Dino-Riders Struthiomimus by TycOMG IT HAS FEATHERS

Quick Facts

1988 Dino-Riders Struthiomimus action figure WITH FEATHERS. IN 1988.

Size: 20cm of feathered glory.

Scale: Scales on the feet, feathers up top. Also, 1:12.

Sculpted by: The wokest of all 1980s dinosaur toy sculptors.

Produced by: Tyco (obviously with a lot of help from Bob Bakker).

No need to adjust your TV sets folks, this is a mass-produced dinosaur toy made in 1988 that is covered in feathers. Not like lame, Primal Carnage, Jurassic Park 3, cool-guy dragon with a mohawk. Natural looking feathers.

This is why Dino-Riders was the best thing about the '80s (sorry, He-Man). Dino-Riders gave us aliens from the future riding armored mind-controlled dinosaurs blasting a thousand lasers at other armored dinosaurs who were not mind controlled but who were just in it because they cared about justice, and the toy versions of these things looked more naturalistic and scientifically accurate (for the time) than anything in Jurassic World.

I'm going to use this particular review to drop some history.

Wednesday, April 5, 2017

Review: Dino-Riders Pterodactyl by Tyco

Quick Facts

1987 Dino-Riders Pterodactyl action figure

Size: 20cm (wingspan)

Scale: 1:3 or 1:4

Sculpted by: unknown

Produced by: Tyco

Pterodactylus antiquus has a special place in history as one of the first ever prehistoric reptiles to be subjected to scientific study. It's one of the best known pterosaurs, with many complete specimens known to science, and it ended up lending its name to the entire group of pterosaurs to which it belongs (Pterodactyloidea). In fact, "pterodactyl" has become a common nickname for all pterosaurs, thanks in part to the fact that nearly all pterosaurs were considered species of Pterodactylus during the 19th century.

Despite the importance of pterodactyls, very few toy versions of them have been produced (in fact I don't know of any other than this one and one made by Starlux - if you know of more, let me know in the comments!). Sure, there are lots and lots (and LOTS) of toys out there claiming to be "pterodactyls", but the vast majority of these are actually other species of pterosaur, most often Pteranodon. A lot of older "pterodactyl" toys from the 1950s - 1980s are weird hybrids of the Pterosaurs' Greatest Hits, like pteranodonts with teeth, or with Rhamphorhynchus tails. But almost none of them are the classic, the original, the one and only pterodactyl. That's probably not a coincidence or a mistake - like the "velociraptors" in Jurassic Park that were really Deinonychus, pterodactyls have a cool name attached to a somewhat wimpy animal. Most pterodactyl fossils are tiny, with wingspans of only a few feet. Larger specimens do exist, but these skin-winged critters don't seem to have grown any bigger than a large seagull. Personally, I think that's part of their charm - I can't help but picture flocks of them squabbling over dead squids any time I watch gulls at the beach. But in terms of raw awesomeness, they certainly can't compete with 20 foot beasts like Pteranodon.

One of the very few pterodactyl toys that's actually a REAL pterodactyl is this one from Tyco. Produced in 1987 and released in 1988 at part of the Dino-Riders line, this pterodactyl came with a 2" action figure and a little hang glider accessory, but I won't be worrying about those here. Despite it's age, this is still one of my favorite pterosaur toys and holds up reasonably well even today. Let's get into some details...

1987 Dino-Riders Pterodactyl action figure

Size: 20cm (wingspan)

Scale: 1:3 or 1:4

Sculpted by: unknown

Produced by: Tyco

Pterodactylus antiquus has a special place in history as one of the first ever prehistoric reptiles to be subjected to scientific study. It's one of the best known pterosaurs, with many complete specimens known to science, and it ended up lending its name to the entire group of pterosaurs to which it belongs (Pterodactyloidea). In fact, "pterodactyl" has become a common nickname for all pterosaurs, thanks in part to the fact that nearly all pterosaurs were considered species of Pterodactylus during the 19th century.

Despite the importance of pterodactyls, very few toy versions of them have been produced (in fact I don't know of any other than this one and one made by Starlux - if you know of more, let me know in the comments!). Sure, there are lots and lots (and LOTS) of toys out there claiming to be "pterodactyls", but the vast majority of these are actually other species of pterosaur, most often Pteranodon. A lot of older "pterodactyl" toys from the 1950s - 1980s are weird hybrids of the Pterosaurs' Greatest Hits, like pteranodonts with teeth, or with Rhamphorhynchus tails. But almost none of them are the classic, the original, the one and only pterodactyl. That's probably not a coincidence or a mistake - like the "velociraptors" in Jurassic Park that were really Deinonychus, pterodactyls have a cool name attached to a somewhat wimpy animal. Most pterodactyl fossils are tiny, with wingspans of only a few feet. Larger specimens do exist, but these skin-winged critters don't seem to have grown any bigger than a large seagull. Personally, I think that's part of their charm - I can't help but picture flocks of them squabbling over dead squids any time I watch gulls at the beach. But in terms of raw awesomeness, they certainly can't compete with 20 foot beasts like Pteranodon.

One of the very few pterodactyl toys that's actually a REAL pterodactyl is this one from Tyco. Produced in 1987 and released in 1988 at part of the Dino-Riders line, this pterodactyl came with a 2" action figure and a little hang glider accessory, but I won't be worrying about those here. Despite it's age, this is still one of my favorite pterosaur toys and holds up reasonably well even today. Let's get into some details...

Monday, July 18, 2016

Playing with Saurian's Genericometer

There's a dinosaur game in development called Saurian. Have you heard of it? You should really check out! It's shaping up to be super cool and extremely rigorous when it comes to science and coming up with accurate portrayals of an extinct ecosystem. Check out their page!*

*Full disclosure: I may be involved in this game's development in some small capacity. There will be birds.

The Saurian developers have made a somewhat controversial choice when it comes to the name of the Hell Creek Formation hadrosaurid. Yes, boys and girls, a video game company has dipped its toe into the boiling caldera that is dinosaur nomenclature. Many fans (and keep in mind these are people who know enough to be early backers of a game priding itself on scientific accuracy and technical minutiae) were a little shocked to see the announcement of the Saurian hadrosaurid. Not just at the unbelievably painstaking level the devs went to in order to research and create the character - everything from life history and growth trajectories to mapping out the actual pattern of scales found on an infamous fossil mummy. People were also a little put off by the fact it was named Anatosaurus annectens rather than Edmontosaurus annectens.

I'm not going to re-hash the long and convoluted history of everybody's favorite "trachodont" (Wikipedia does a pretty good job of that). For the purposes of this post, it's enough to understand that these two species of dinosaurs, Anatosaurus annectens and Edomontosaurus regalis, are fairly similar. So similar that for the past 25 years or so, most scientists have "lumped" them together under the same group of species, the genus Edmontosaurus, making the binomial of the Hell Creek Formation species Edmontosaurus annectens and relegating the name Anatosaurus to the trash heap of history.

But, a few years ago something changed. See, there was a second Hell Creek hadrosaurid, a bigger and much more different looking beast named Anatotitan copei. During the same 25 year period, mostly everybody has agreed this dinosaur was different enough from its relatives to deserve its own genus name. Recently, studies have demonstrated that those differences aren't necessarily due to being more distantly related, but just being... older. Anatotitan, it turns out, is just a mature version of Anatosaurus/Edmontosaurus annectens that had built up more unique features with age. It's not just a similar species to annectens, like Edmontosaurus reglais is, it's the same species. So onto the trash heap with Anatotitan.

But wait! Anatosaurus was thrown out because it was too similar to Edmontosaurus. Now, it turns out, it was actually different--different enough that its adult form was given its own genus for all those years. So shouldn't Anatosaurus be a genus again?

Well, that depends on what you mean by "genus". There is no universally recognized rationale for what makes something "different enough" to be a genus, and the concept varies wildly between fields of biology. Each scientist has their own opinion, their own gut feeling based on tradition and intuition, not science, of what a genus should be. If you asked an entomologist to re-classify all dinosaurs based on her own personal "genericometer" settings, we'd end up with one single genus of dinosaur, and it would include every bird that ever lived. Probably crocodiles too. We'd be left arguing, based on page priority or something, if the star of Jurassic Park should be called Passer rex, Vultur rex, or Crocodylus rex. On the flip side, if you had a ceratopsian worker reclassify the beetles, we'd end up with a hundred billion new genera of beetle.*

*I'm not 100% sure that's the correct number, but it'd be something with a lot of zeroes.

Some people have attempted to bring some science to the art of taxonomy, and quantify genera. Recently and most famously, Emanuel Tschopp and colleagues published their precise genericometer settings, and used those settings to reclassify the diplodocid sauropods. This resulted in bringing back the old, previously-junked genus name Brontosaurus (you may have heard of it). This is a great thing to try, but the method was only designed to apply to diplodocids. It might wreak havoc with names in other dinosaur groups, and would certainly result in an entomologist revolt if anybody ever tried to use it on bugs.

To their credit, the Saurian team have been up front with their genericometer settings used in the game. Rather than base their concept of genus completely on anatomical similarity, they've made the very intriguing choice of combining evolutionary relationships with a chronological component. Basically, if species B is the closest relative of species A, and if species B is known from fossils that can be dated to within one million years of species A fossils, then species A and B are to be classified in the same genus.

I thought it would be fun to try out these genericometer settings and see how it compares to the current traditional consensus, and to some other more widely criticized attempts to re-genericize dinosaurs, like the classification used by Greg Paul in his Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs.

|

| Edmontosaurus vs. Anatosaurus. |

We'll start with Anatosaurus. If we take Anatotitan to be its synonym, then according to most recent phylogenies, its closest relative is Edmontosaurus regalis, which lived more than a million years earlier. This is why Saurian chose to split Anatosaurus back off into its own genus. But right here, we immediately need to note how highly dependent on the vagaries of phylogenetic analysis this method is. Ugrunaaluk is a very similar hadrosaurid that actually lived in between Edmontosaurus and Anatosaurus, and was originally thought to represent specimens of Edmontosaurus. According to the (very few) phylogenetic analysis on its relationships, Ugrunaaluk is actually outside the Anatosaurus+Edmontosaurus clade. But, given its chronological position, it's always possible more analysis will show that it is transitional between them. Ugrunaaluk is still too old to connect Anatosaurus to Edmontosaurus by a million years or less, but only slightly. Ugrunaaluk lived about 69 Ma ago, and the earliest Anatosaurus fossils are about 67 Ma old. All it would take would be one slightly younger Ugrunaaluk specimen, in that case, to pull the whole shebang back into Edmontosaurus.

Following this cladogram for the sake of argument, let's look at the next outgrip to Edmontosaurus, which is the clade Saurolophini. Now we reach the sticky question of what counts as the next closest relative of Edmontosaurus, moving down the tree. So lets start at the tip of the next branch, with Saurolophus. S. osborni lived between about 69-68 Ma ago, slightly later than the last Edmontosaurus, but still within a million years. S. angustirostris lived about 70 Ma ago, during the time Edmontosaurus was alive. Prosaurolophus lived up until around 74 Ma ago, which predates Saurolophus but sits just barely within a million years of the lower range of Edmontosaurus. Since both Saurolophus and Prosaurolophus lived within a million years of the upper and lower range of Edmontosaurus, following these genricometer settings, they should all be lumped into a single genus. Because of the rules of priority, that means Edmontosaurus itself goes on the trash heap and Saurolophus regalis becomes the correct name for that species. Same for the next closest relative to the Saurolophus + Edmontosaurus group, Gryposaurus, which is within a million years of Prosaurolophus. Ditto Kritosaurus. It's not until the Brachylophosaurini clade that we finally get a break from all this lumping, but already, half of the short-crested hadrosaurids are now Saurolophus.

Obviously, I'm taking this a little far on purpose, just to test it out as a general-use genericometer for dinosaurs. You could easily tweak these settings to produce more traditional genera, like adding a rule against paraphyly (both Anatosaurus and Kerberosaurus would fall within a clade formed by members of Saurolophus in the above example; though in my opinion this is a feature rather than a bug, since some genera had to have evolved from others anyway, it's a little silly trying to rigidly keep them monophyletic). We could also add a stipulation that the time component is relative to the type species or, even better, type specimen, to allow for inevitable evolutionary grades from one form to another. This would, in effect, place a sort of million-year "radius" around a species that is not ever-expanding. So anything up-tree or down-tree of E. regalis, like Ugrunaaluk, gets caught in its gravity well, but we don't then jump to anything within a million years of Ugrunaluuk, too. I have to think this is probably the real intent of the Saurian team's method.

|

| A variety of ceratopsid genera, by Danny Cicchetti (CC-By-SA). "These are all different GENERA? That's hilarious," --Entomologists. |

Using this type-restricted genericometer method could still do some fun things in the one part of the dinosaur tree that everybody sort of secretly thinks is horribly over-split but doesn't say so out loud because nobody really wants to rain on those guys' big ol' naming party: the ceratopsids.

The Saurian team stated that, if they were to include Torosaurus as a distinct species in the game, it would be as a species of Triceratops, per the genericometer settings described above. Following this cladogram and a type-restricted interpretation of Saurian's method, Torosaurus does become a species of Triceratops, the holotype of which is from about 67 million years ago. Nedoceratops has to go as well. Now, the Triceratops party ends there based on this particular cladogram, but I find the placement of the Titanoceratops a little er... iffy. Titanoceratops is really, really similar to Pentaceratops from almost the same time and place, so finding it in between a bunch of species that look basically identical to Triceratops is odd. I'm not saying it's wrong, but let's just ignore it for the moment. If we do, then Ojoceratops, Eotriceratops, and Regaliceratops all become species of Triceratops, too. So the entire clade Triceratopsini = Triceratops.

Further down the tree, we have Anchiceratops and Arrhinoceratops becoming synonyms. Kosmoceratops and Vagaceratops, too. Chasmosaurus subsumes Mojoceratops, Agujaceratops, Utahceratops, and Pentaceratops. Coahuiloceratops and Bravoceratops are both safe, and form the sister clade to the big Chasmosaurus complex.

On the centrosaurine side of the tree, Achelousaurus becomes Einiosaurus, unless paraphyly is invoked. Centrosaurus gobbles up Coronosaurus, Spinops, and Styracosaurus (again, unless paraphyly is invoked, in which case Styracosaurus remains valid but includes Rubeosaurus ovatus; this was the plan for one of the unmet Saurian Kickstarter stretch goals that would have included Styracosaurus ovatus).

Overall, this system produces a classification that is similar to, but not nearly as extensively lumped, as the one used by Greg Paul. I kind of like it, especially with the type species stipulation in play. I think that if you are going to use genera, and not just convert all genus names to species praenomen as some people have suggested, it's a good idea to have some kind of standard metric. The problem is, of course, that nobody will ever agree to one standard. Even within dinosaurs. Nobody specializes in all dinosaur groups. We have ceratopsian workers, tyrannosaur workers, avialan workers, sauropod workers, etc., all with their own traditions and personal metrics. This is why it tends to be the science popularizers, like the Saurian devs or Greg Paul or even Bob Bakker, who are the ones coming up with what all the professionals view as highly idiosyncratic classifications. They're attempting to take all these disparate fields within dinosaur paleontology and apply a single metric to all of them, which is bound to change a few things away from the consensus.

At the end of the day, the consensus is what it is. I'm glad people are exploring ways to apply consistency and standards to science-related minutiae like taxonomy. But it's equally important that those efforts be transparent, so we can compare each metric to the others and see which produces the results we like the best. Because at the end of the day, all of this splitting and lumping of genera comes down to just that: a matter of opinion.

Saturday, May 28, 2016

You're Doing It Wrong: Microraptor Tails and Mini-Wings

|

| Type specimen of Zhenyuanlong, doing its best Archaeopteryx impression. |

Microraptor was the first time we got a good look at the feather pattern of dromaeosaurids. This is a big problem for two reasons. One, microraptors were small. That means that artists who were looking at them to extrapolate for bigger, more famous "raptors" could easily and somewhat justifiably write off their huge wings as a product of their size. Sure, we thought, microraptors had big wings, but they're tiny animals. Surely the bigger, more terrestrial dromaeosaurids didn't need such big wings. They probably still had wings, but they'd be smaller. Why would Velociraptor need such proportionately huge wings if it couldn't fly or glide?

Meme number two: that tail. I admit to being one of the first to go overboard when I fell, head over heels, for the "puff tailed dromeosaur" fossil (now the holotype of Cryptovolans, a synonym or close relative of the Microraptor) back around 2000. This was the first evidence we had of the tail feather style in dromeosaurids (or evidence that they even had remixes and rectrices at all. Remember When Dinosaurs Ruled America? That was plausible at the time it was being made). Naturally, having Microraptor plus Caudipteryx showed that the ancestral condition of pennaraptorans was a fan of feathers at the tip of the tail, not a fuzzy Sinosauropteryx like tail or a fully-vaned Archaeopteryx like tail. So artists ever since have been drawing dromeosaurids and troodontids and oviraptorosaurs with microraptor tails.

But that turned out to be wrong! It's an accident of history. We're now learning that Microraptor and Caudipteryx are weirdos.

Sunday, May 1, 2016

The First Feathered Dinosaurs (In Art)

|

| The first illustration of a hypothetical "pro-avis" by Pycraft, 1906 |

|

| Nopcsa's 1907 feathered, Compsognathus-like "pro-avis" model at the Grant Museum, London. |

|

| Beebe's "tetrapteryx", 1915. |

|

| Speculative reconstruction of a Triassic "carnavian" dinosaur leaving feather traces in its trackway, from Ellenberger 1974. |

The thecodont origin of birds did not truly give way to a dinosaur origin until the 1970s, after John Ostrom described the similarities between Archaeopteryx and Deinonychus. If dinosaurs were the new closest relatives of birds, then at least the most bird-like among them should be depicted with feathers (Ostrom himself disagreed with this though, and, according to Bakker, he fought the idea that Deinonychus should be feathered). Of course, which dinosaurs were most closely related to birds, and just how much of a gap remained between them and Archaeopteryx, allowed for considerable wiggle room and speculation.

|

| A "carnavian" track maker parachuting, from Ellenberger 1974. |

|

| Landry's influential 1975 restoration of "Syntarsus". |

|

| "Syntarsus" by Stout, 1976. |

One of my favorite derivatives of Landry's Syntarsus illustration is one made in 1976 by William Stout and reproduced in Don Glut's 1982 edition of The New Dinosaur Dictionary. Though Glut pointed out that the feathers were speculative, they're probably less inaccurate than the legless snake it's eating! Also included in Glut's revised dictionary was one of the first illustrations of the theropod Kakuru, by Mark Hallett. Though just as speculative as Ellenberger's drawing (Kakuru is known only from two limb bones), it has more of a modern feel. The reclining theropod is decked out in long, filamentous feathers, rather than the broad, scale-like feathers of Landry's Syntarsus. It's worth noting that all of these early drawings of feathered dinosaurs had bare or scaly faces. This method of emphasizing the transitional character of early feathered theropods was probably inspired by traditional portrayals of Archaeopteryx, a "bird" with the head of a "reptile."

|

| Feathered ornithischians, by Lorene Bjorklund, from The Warm-Blooded Dinosaurs, 1979. |

A few very early books featuring extremely prescient feathered dinosaurs came in 1978 and 1979. First, Julian May brought us perhaps the first renaissance-era dinosaur book for kids, The Warm-Blooded Dinosaurs, which featured not only a feathered Struthiomimus by Lorene Bjorklund on the cover, but several feathered ornithischians inside. An Iguanodon looks sort of ambiguously feathered (it might just be the crosshatched style), and interestingly, has a abrupt transition to a croc-scutes tail very similar to Kulindadromeus. There's also a skeletal of Microvenator with a fuzzy, Greg Paul style silhouette outline. The next year, Archosauria: A New Look at the Old Dinosaur by John McLoughlin includes some species with feathered faces for the first time, like his amazing, feathered Coelurus. It's odd as a modern reader to see that in both of these books, it's the more basal dinosaurs shown with feathers. Primitive ornithopods and "coelurosaurs" (considered a paraphyletic grade of early, ancestral dinosaurs at the time) like Syntarsus, Coelurus, and Saltopus are given feathers while deinonychosaurs like Saurornithoides and Deinonychus are not. The influence of the thecodont theory was still going strong, with birds thought to have evolved from the earliest dinosaurs rather than deinonychosaurs, which were exclusively known from the Cretaceous at that time.

|

| Kakuru by Mark Hallett, from Glut 1982. |

After Syntarsus, the next non-avialan to become consistently depicted with feathers was Avimimus. From its first discovery, Avimimus was interpreted (and in some cases, like the supposed lack of a tail, misinterpreted) as being as birdlike or more than Archaeopteryx. Though commonly misreported online as having quill knobs, Avimimus actually had a flat ridge on the ulna which has been interpreted as a similar kind of support for the soft tissue of a feathered wing. Though not the same kind of direct evidence as quill knobs would be, most paleoartists ran with the suggestion, and most early Avimimus illustrations did portray it with feathers. John Sibbick restored it that way for David Norman's 1985 Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, and his version is a down-right throwback to the "pro-aves" of the early 1900s, with long, scale-like feathers on the outstretched arms and tail.

|

| The first(?) feathered Deinonychus, a statuette by Otter Zell, 1984. |

|

| Two early restorations of Avimimus. Left: by Sergai Kurzanov, looking very bird-y. Right: By John Sibbick from Norman's Encyclopedia, looking very much like Heilmann's "pro-avis." |

|

| A modern feathered dinosaur: Tianyulong sculpture by Jason Brougham, 2016. |

Sunday, November 30, 2014

Is Jurassic World Stealing from Independent Illustrators?

Sorry for the clickbait title. The answer is yes. Yes they are.

It's one thing when toy companies do it.

It's quite another when a big-budget Hollywood movie starts stealing the work of independent paleoartists and illustrators for use in their production design.

It started when well-known paleo illustrator Brian Choo posted the following modified production still to his DeviantArt account. The photo in question is fairly low res and comes from the newly opened Jurassic World web site. The still features children using a prop in the movie called a "Holoscape", presumably a kind of interactive computer terminal featuring information about the various kinds of dinosaurs in the park.

It's one thing when toy companies do it.

It's quite another when a big-budget Hollywood movie starts stealing the work of independent paleoartists and illustrators for use in their production design.

It started when well-known paleo illustrator Brian Choo posted the following modified production still to his DeviantArt account. The photo in question is fairly low res and comes from the newly opened Jurassic World web site. The still features children using a prop in the movie called a "Holoscape", presumably a kind of interactive computer terminal featuring information about the various kinds of dinosaurs in the park.

Saturday, October 11, 2014

You're Doing It Wrong: Protobird Toys Edition

|

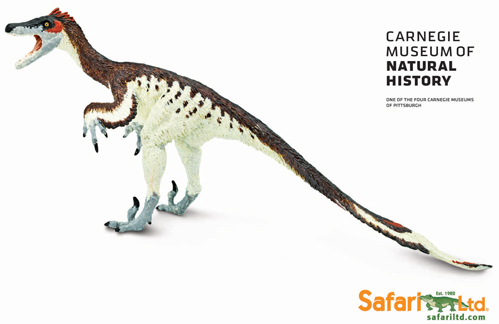

| The new Carnegie Velociraptor figure. |

Let me preface this post with a few disclaimers. One, I have no problem with people making dinosaur art however they like. But I feel it's very important to draw a distinction between dinosaur art in general and paleoart. Creating a drawing, painting, or sculpture under the guise of paleoart implies that some degree of research went into the piece. When evaluating paleoart, critics are completely entitled to demand as rigorous an approach to accuracy as the evidence allows. Of course, speculation must be included to some degree, but the baseline expectation is always that basic facts and plausible inference will be taken into consideration.

Dinosaur art is a for of pop art, a purely artistic expression. Paleoart is a representation of a scientific hypothesis about the life appearance and behavior of an extinct organism.

This recent Twitter kerfuffle was due specifically to the debut of a new dinosaur figure in the Carnegie Collection produced by Safari Ltd. I've been a big fan of the Carnegie figures (and the sometimes nicer quality Wild Safari sister series) since I was a wee lad buying my first Carnegie Pteranodon in a little hobby shop for about $2, and pining over their massive Brachiosaurus. Carnegie figures have obvious appeal for scientifically-minded young dinosaur fans. First, most of them are made with a consistent scale (usually 1:40), so when you line them all up you can see how big each animal was compared to one another. Second, they are marketed as having the highest level of scientific authority: the Carnegie Museum stamp and assurances that hey are approved by actual paleontologists gives them the weight of authority and accuracy not found in many other toy lines. Sure, many of the older figures, including my Pteranodon, are now sorely out of date, but this is due largely to the Science Marches On effect rather than a basic, original inaccuracy.

However, like many paleoartists, the sculptors at Carnegie and related accuracy-minded/marketed toy lines seem to be having, well, let's say a little trouble adapting to the feathered revolution. Trained in the '80s and '90s drawing and sculpting Paulian, reptilian dinosaurs, it's been a steep learning curve for many of these artists to switch to bird-like, feathered dinosaurs, which many artists don't even realize requires a crash course in avian anatomy, rather than reptile or mammal anatomy, to get right. This is why expert consultants are so important in these projects--artists simply need help catching up with the latest research. Unfortunately, they're usually getting bad advice from "experts" who simply do not care.

The newest entry in the Carnegie Collection is the old favorite Velociraptor. Carnegie had previously released a scaly Velociraptor, but like many of their other models, they have commendably updated it to try and reflect current science. Unfortunately, it seems they mainly achieved this by slapping feathers over the basic original model with no regard for the fact that feathers inherently change the entire presentation and outline of an animal. Unlike fur or "protofeathers", which just fluff up the outline of an animal, feathers are more like a mobile exoskeleton that re-defines the entire body.

|

| My own hypothesis, based on fossil and phylogenetic evidence as well as inference from living analogues, about the life appearance of Velociraptor. |

Specifically, the wings in the new Velociraptor figure are very small, with short feathers, and are present only on the forearm, not the hand, making them only half a wing--literally, since they're issuing the primary feathers. We do not have direct evidence of primaries, but we have never found a single example of a maniraptoran that has secondaries but not primaries, and so it should be assumed they were there by default. As for secondaries, we have direct evidence in the form of quill knobs for this species. Quill knobs are not found in all feathered animals, let alone all flying birds, and seem to be associated with strong attachment either due to high-stresses during flight or other flapping behavior and/or especially large/long individual feathers.

Long story short: Not only did Velociraptor have wings, it probably had larger wings than many other dromaeosaurids. AFAIK not even Microraptor and Archaeopteryx had quill knobs to support their wings.

The new Carnegie figure, on the other hand, barely has wings at all. What went wrong?

Some insight can be gained by a recent series of incidents involving sculptor Dan LoRusso on the message board of the Dinosaur Toy Blog. LoRusso Is an amazing artist and is responsible for some of my all-time favorite dinosaur figures released in the Boston Museum of Science Collection by Battat (now being re-released with updates and new figures under the Terra brand). Collectors were understandably excited about the fact that the Battat series was coming back after nearly two decades, though the excitement was dampened a little by some obvious accuracy issues in the new figures, specifically when it came to the feathered species (or species that should have been feathered).

LoRusso was criticized online for producing a very well done but very inaccurate therizinosaur figure which completely lacked feathers. It would have fit right in with the excellent quality and Paulian style of the original series... back in 1994. But in 2014, when we have incontrovertible proof that therizinosaurs were not only feathered but that at least smaller species were very densely feathered, it is simply bizarre to see a featherless figure in a line that is being marketed as scientifically accurate. LoRusso stated that his consultants told him larger therizinosaurs would have been featherless. It's not LoRusso's fault that he somehow was able to sculpt a bald maniraptoran in the year 2013. Somebody who did not know what they were talking about and claiming to be an expert in paleoart just because they work in the related field of paleontology told him to do it, and he very reasonably believed them because they were an "expert", though obviously they had misrepresented themselves.

And there's the biggest problem and probably the answer to the question of what is going on with these strange and obvious inaccuracies. Paleoart consultants for major projects tend to be, often but not always, simply terrible. They seem not to know what they are talking about. Not only that, but second-hand reports suggest that they often simply do not care. Seriously: When asked about blatant inaccuracies creeping into paleoart-based projects like toys or books or even press releases, at least one anonymous paid paleontological consultant stated that they don't care what dinosaurs looked like in life, and so would presumably rubber-stamp any abomination that came across their desk.

@mpmartyniuk You know I've spoken to working palaeontologists who even say that they >don't care< about depicting life appearance?

— Darren Naish (@TetZoo) October 4, 2014

Here's a prime, objective example: The Carnegie Collection Caudipteryx zoui figure. This species was first found in 1998, a complete skeleton with feather impressions. There are plenty of photos of Caudipteryx fossils that show crystal clear how the feathers attach and were ignored completely for this figure. The artist might have copied some inaccurate depiction rather than doing actual research or glancing at a fossil, and the consultant approved it because they didn't know or didn't care about the relevant details. The Carnegie Caudipteryx proves that consultants are utterly useless and often have no clue what they're talking about. Any one of us can compare the model with the fossil and show that the model is objectively wrong in major details. Look for yourself: |

| Caudipteryx wing fossil: note the primaries, longer than the hand, anchored along the second finger, and lack of a clawed third finger. |

|

| Carnegie Collection Caudipteryx figure. Note the wing feathers anchored everywhere along the arm EXCEPT on the second finger where they belong, and the incorrect number of fingers. |

It's not fair to ask all working paleontologists to know or care how their research into fossils translates into life appearance. Matching osteological and behavioral correlates with the structure and anatomy of living analogues could almost be considered a distinct field separate from actual paleontology. This is something paleoartists can and do think about and research constantly, but would almost never need to enter into the research when describing fossils. There's really no reason for working paleontologists to keep up to date with developments and research that go into paleoart.

The solution? Don't ask these paleontologists to consult! Just because someone is a paleontologist does not make them an expert on the life appearance of any given species of prehistoric organism. The examples cited above were, allegedly, all approved by "expert" consultants. This simply proves the consultants that are being employed are utterly failing at their job. I hate to say it, but there are legions of paleoartists and other dinosaur fans online who jump at the chance to criticize and nitpick and otherwise consult on these things for free. It's just that by the time the product is released, it's too late to do anything about inaccuracies. If companies that use paleoart would simply post concept art beforehand on, say, Facebook, they could probably get much better advice for free. Or, preferably, they could employ actual paleoartists as experts, hopefully artists who specialize in researching the life appearance of a given subject group of organisms.

Darren Naish, Mark Witton, and John Conway recently published an article on the (shameful) state of paleoart as used in professional and commercial contexts. Companies like Safari Ltd. would do well to listen to their advice.

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

People Think Feathered Dinosaurs Don't Look Scary. They're Right.

This short article on io9 pretty well encapsulates an area of frustration for artists and scientists in the age of feathered theropods.

The implication is, right from the title, that it's common knowledge most depictions of feathered T. rex are not cool. Feathered theropods are widely derided by the public because feathers make these scary reptilian monsters less scary. In a recent Facebook discussion, I took one of those "short pelt raptor" images to task for inaccuracy (you know, the kind that pays lip service to the idea of feathered theropods, but with the minimum possible change to the classic silhouette, with a cat-like short pelt rather than a bird-like poof of feathers engulfing the body). In my reply I kind of hypothesized that there's an evolutionary psychology* reason for our aversion to feathered theropods and our cat-like concessions to the idea.

As Andrea Cau has pointed out, paleoartists (myself included), consciously or not, often employ all kinds of subtle tricks to make feathered theropods look "cool". Leaving the face scaly and reptilian is a popular trick; his body might say "Big Bird", but his face tells you he means business. Face fully feathered? Introduce an eagle-like lowered "brow" or some kind of eyebrow analogue so his facial expression can look "mean". Make sure his mouth is open or he's prominently displaying his other weapons in a ninja-like fighting stance. And be sure if you make him colorful, use high contrast, red and black if possible, and light it so his face is in shadow--that way you know he's thinking evil thoughts. This might also allow you to add eye shine making the eyes look like demonic embers! (check back to the io9 article and see how many of these points that T. rex hits).

In the comments to the io9 article, there were the predictable bouts of resistance to the idea that T. rex could have had feathers at all. "It was too large! Large mammals don't have so much fur in hot climates!" The problem with comparisons to large mammals is that feathers are very different in structure from fur, and have very different insulating properties. Fur is mainly used to keep an animal warm, but thanks to the fact that feathers grown in adjustable, planar layers, and are better at trapping and regulating air flow, many large birds use their feathers to very effectively keep themselves cool by circulation while blocking the skin from absorbing direct sun. It may actually have been disadvantageous for a large animal to lose its feathers, especially if it lived in a hot sunny climate. The fully-feathered Yutyrannus was not significantly smaller than any but the largest T. rex. Most T. rex specimens fell short of the 6.8 tons estimated for the most gargantuan known adults like Sue, that is certainly not the species average size!

But, there was one comment that played right into my ego-psych hypothesis. The commenter basically stated that we know juvenile T. rex had feathers, but there's no reason to think adults kept them. Except even that premise is wrong. There is in fact zero direct evidence to support the hypothesis that T. rex juveniles had feathers, let alone that they had them and then lost them. It's simply easier for people to assume that a baby animal, which is supposed to be cute, had feathers, which we psychologically associate with cute animals.

It is actually less of a stretch (i.e. more parsimonious) to hypothesize that based on its phylogenetic bracket, T. rex had feathers and retained them throughout its life, than the hypothesis that T. rex was born with feathers, lost them because they became disadvantageous at some unspecified weight, then through some unknown developmental pathway replaced its feathers with the kind of thick, scaly skin it is usually depicted with and would need to protect itself from the sun/injury if it lacked feathers. But this convoluted thinking is easier for people to accept because T. rex is the king of all monsters, and monsters are by definition not cute.**

The sad fact is, T. rex may not have looked all that cool. I think John Conway and others have brought this up before. It, and many if not most other dinosaurs, may very well have looked really, really stupid to us. Nature doesn't care if an animal looks intimidating to a species that evolved 66 million years later in a completely different environmental context alongside a vastly different set of predators. Our brains are programmed to find mammalian and reptilian predators scary at least in part* because we evolved alongside these and our survival depended on it. We had no such pressure for most kinds of birds***, and maybe coincidentally, we find very few kinds of birds the least bit intimidating. We have to be told/shown that a cassowary is even capable of being dangerous, and people still constantly trot this out as a surprising fact, despite the fact that it has very few physical differences from a Velociraptor, other than being much larger!

So, if your average Joe met a non-avialan theropod in real life, the reaction might be less like any of the raptor scenes in the original Jurassic Park and more like Newman vs. the cute, colorful, silly, hopping (read: bird-like) dilophosaur - bemusement leading to injury.

* I know evo psych is mostly made up of untestable just-so-storys. But it's still fun to think about.

** That's sarcasm. Tyrannosaurs were not monsters, they were plain old regular animals. A lesson people forget from the original Jurassic Park (probably because they're not actually depicted hat way in the movie, despite the fact that the characters talk about it).

***Raptors seem to be the exception. Probably because they preyed on early humans, and maybe also because of their mean-looking "eyebrows"?

|

| Ooh, I'm shakin' in my boots. Photo by Simon Rumble, licensed. |

As Andrea Cau has pointed out, paleoartists (myself included), consciously or not, often employ all kinds of subtle tricks to make feathered theropods look "cool". Leaving the face scaly and reptilian is a popular trick; his body might say "Big Bird", but his face tells you he means business. Face fully feathered? Introduce an eagle-like lowered "brow" or some kind of eyebrow analogue so his facial expression can look "mean". Make sure his mouth is open or he's prominently displaying his other weapons in a ninja-like fighting stance. And be sure if you make him colorful, use high contrast, red and black if possible, and light it so his face is in shadow--that way you know he's thinking evil thoughts. This might also allow you to add eye shine making the eyes look like demonic embers! (check back to the io9 article and see how many of these points that T. rex hits).

In the comments to the io9 article, there were the predictable bouts of resistance to the idea that T. rex could have had feathers at all. "It was too large! Large mammals don't have so much fur in hot climates!" The problem with comparisons to large mammals is that feathers are very different in structure from fur, and have very different insulating properties. Fur is mainly used to keep an animal warm, but thanks to the fact that feathers grown in adjustable, planar layers, and are better at trapping and regulating air flow, many large birds use their feathers to very effectively keep themselves cool by circulation while blocking the skin from absorbing direct sun. It may actually have been disadvantageous for a large animal to lose its feathers, especially if it lived in a hot sunny climate. The fully-feathered Yutyrannus was not significantly smaller than any but the largest T. rex. Most T. rex specimens fell short of the 6.8 tons estimated for the most gargantuan known adults like Sue, that is certainly not the species average size!

But, there was one comment that played right into my ego-psych hypothesis. The commenter basically stated that we know juvenile T. rex had feathers, but there's no reason to think adults kept them. Except even that premise is wrong. There is in fact zero direct evidence to support the hypothesis that T. rex juveniles had feathers, let alone that they had them and then lost them. It's simply easier for people to assume that a baby animal, which is supposed to be cute, had feathers, which we psychologically associate with cute animals.

|

| Are one of these things is not as scary as the other? Illustrations by M. Martyniuk, all rights reserved. |

The sad fact is, T. rex may not have looked all that cool. I think John Conway and others have brought this up before. It, and many if not most other dinosaurs, may very well have looked really, really stupid to us. Nature doesn't care if an animal looks intimidating to a species that evolved 66 million years later in a completely different environmental context alongside a vastly different set of predators. Our brains are programmed to find mammalian and reptilian predators scary at least in part* because we evolved alongside these and our survival depended on it. We had no such pressure for most kinds of birds***, and maybe coincidentally, we find very few kinds of birds the least bit intimidating. We have to be told/shown that a cassowary is even capable of being dangerous, and people still constantly trot this out as a surprising fact, despite the fact that it has very few physical differences from a Velociraptor, other than being much larger!

So, if your average Joe met a non-avialan theropod in real life, the reaction might be less like any of the raptor scenes in the original Jurassic Park and more like Newman vs. the cute, colorful, silly, hopping (read: bird-like) dilophosaur - bemusement leading to injury.

* I know evo psych is mostly made up of untestable just-so-storys. But it's still fun to think about.

** That's sarcasm. Tyrannosaurs were not monsters, they were plain old regular animals. A lesson people forget from the original Jurassic Park (probably because they're not actually depicted hat way in the movie, despite the fact that the characters talk about it).

***Raptors seem to be the exception. Probably because they preyed on early humans, and maybe also because of their mean-looking "eyebrows"?

Sunday, May 18, 2014

Review: Papo Archaeopteryx

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Did Jurassic Park Name T. rex?

|

| T. rex illustration by Matt Martyniuk, licensed. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)